Studying this important book, I was especially struck by Christian's poetic and imaginative approach to music playing that so beautifully blends hands-on tips for specific lyre playing techniques (such as exercises for the seamless use of the right and left hands, and learning to know the right timing for damping the strings) with his gentle way of assisting in the cultivation of one's musical sensibility in general. Even the title of each one of the 18 exercises is intriguing, curious and evocative, and I still remember six years later how I felt when I studied some of these exercises. For example, No. 8 is titled as "You are Gone, but I Still Love You," and according to Christian, it is an exercise to experience "the movement you execute before [making musical sound], that is actually the music itself." (Paths of Sound, p. 10.) No. 14, on the other hand, is an exercise with a humorous title, "Two [People] who Do Not [Understand] Each Other, Or?" meant to help in the exploration of dynamics on the lyre. No. 15, "In the Evening" invites us to "listen to softly ringing bells in the cooler air, [when] someone is calling from afar." The effective use of the interval of the major second sounds like ringing bells, and when one can picture that in the music one is playing, the imagination becomes endless.

Overall, the biggest characteristic in Christian's lyre teaching is his strong emphasis on the importance of learning how to sing on our instrument, i.e. how to sing a melody. Anyone who plays a musical instrument knows that this is one of the most important aspects in playing music, and we all need to learn to execute this by finding the best way to use our physical bodies to play our respective musical instruments, be it the piano keys, lyre strings, or violin bow, while using imagination and our listening capacity to assist with such highly specialized physical movement.

So like any other fine music teachers, Christian advises us to "hear the next phrase in advance" and "listen before we make sound." In order to learn to achieve such singing quality in one's lyre playing, In Exercise 9, titled "Playing–Listening–Silence," he asks us "to take time" in playing melodies. I still remember vividly how different and refreshing it was to play Exercise 9 on the lyre. Having played the piano and the flute all my life as an amateur musician, I felt humbled at first that there are not so many tones on the lyre and that these were quite simple melodies, yet when I played this exercise again and again, observing Christian's instruction, I found myself experiencing each single tone as a living being, it was something I had never experienced qualitatively with the piano or the flute, that I could feel the presence of the sound and the melody I was playing on the lyre.

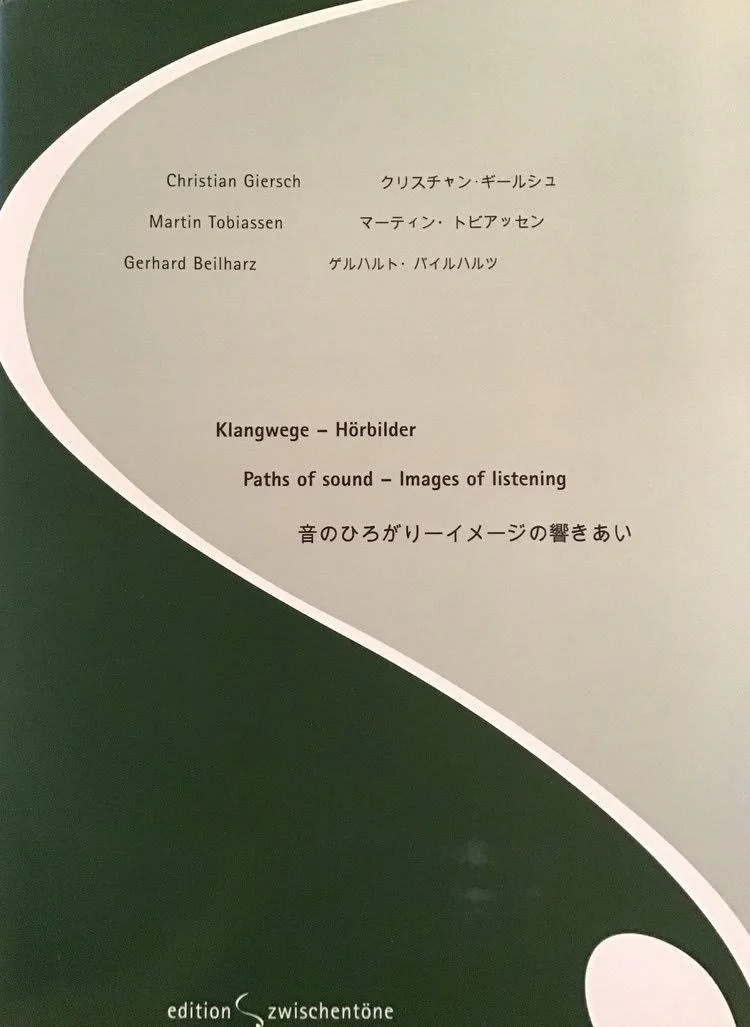

After I finished studying this book, I did not wait too long to start going to Germany to study with Christian and Martin Tobiassen in person. Since 2019, I have gone to Christian and Martin's Summer Lyre Academy for Artistic Playing of the Lyre nearly every summer, except for 2020 when traveling overseas was impossible. Every year, we have gathered in this music-friendly, privately owned castle near Würzburg and stayed there for one week, while working on various solo, ensemble, and plenum pieces, which culminate in a public sharing on the last day. Over time, I have worked on various musical pieces under Christian and Martin's supervision, but what I have found most admirable in working with Christian, especially when he conducts our plenum pieces, is his "awakening and consolation" approach in selecting music.

The modern lyre is a new musical instrument, having been born in Dornach in 1926, and not only its sound, but its music is relatively new. Every year at the Academy, we have explored original lyre music by mostly anthroposophic composers such as Jan Nilsson, Volker Dillmann, and Lothar Reubke. A most memorable experience for me was to play Christian's own piece, "12-tone Canon," the sounding of which was so new and eye-opening that once I learned it, it was impossible not to hear it in my head for a long time. When presenting lyre music in a concert, Christian always combines such pieces that require some new attitudes toward listening with more classical pieces (hence "consolation"). For the latter group, every year we play pieces by such composers as Bach and Händel, mostly in four voices. One summer, Christian conducted us playing Mozart's "Priests' March" from the Magic Flute, which was delightful, as well as Samuel Barber's "Adagio," for which we as a group practiced to sing a melody together, like a snail movement. He also brought us classical pieces by lesser known composers such as Fanny Hensel and Wesselin Stojanoff, and every summer we have some surprises. I strongly believe that this practice of presenting both experimental, original lyre pieces along with classical pieces needs to be explored more here in the US, where I feel not many people actually know that a small lyre orchestra can play such a wide variety of music.